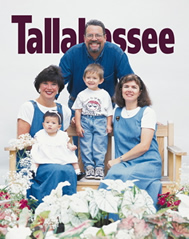

By Kathy Grobe, Tallahassee Magazine, July/August 1999

Rich and Teresa Fillmon became acquainted with Ukraine and its people through the Meridian Woods Church of Christ, where they are members. They came to know a people who need much and ask for nothing after missionary trips to the area; they soon realized that, as Teresa Fillmon says, “the key is to get those kids out of there.” A family of deep faith, the Fillmons acknowledged the Scriptural admonition in James 1:27 to “look after orphans and widows” as further motivating them to adopt a Ukrainian child.

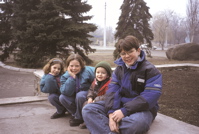

Fellow church members Faye Howell and Michael Webb and Howell’s daughter, Lauren, joined the Fillmons in their Ukrainian odyssey. To adopt 4-year-old Artur, the Fillmons and their friends surmounted bureaucratic snafus, state holidays, a language barrier and several 22-hour train rides.

“A Ukrainian adoption actually takes only 3 1/2 weeks,” Teresa says, “but we were at a time disadvantage from the start because we missed our plane (in Tallahassee), and then they lost our luggage.”

As annoying as all that was, it was just the beginning. The previous October, Teresa had traveled to Ukraine with a shipment of humanitarian aid – medicine, toiletries and other simple necessities that we often take for granted. “What about adopting a Ukrainian child?” Rich had asked her before the trip. He urged her to “look around, be open” to the possibilities.

All Ukrainian adoptions start at the Adoption Center in Kiev, the capital, Teresa relates. The normal procedure is to inform officials the age range of the children you’re interested in and to let them know if you prefer to adopt from a specific region of the country. Then you see pictures of children from that area who might meet your criteria; you’re invited to visit the children and make your selection.

“Although you are not allowed to pre-select a child for adoption,” Teresa says, “I felt that (in October) the Lord had led me to a boy in Dzerzhinsk named Anatoly. Our church supports the orphanage there, and I had every intention of going over and picking up Anatoly.” To begin with, the Fillmons traveled to Ukraine and their friends, the Howell-Webb family, journeyed as far as Prague, in the Czech Republic, where they waited to learn how they might help out.

The Best-Laid Plans

Although the Fillmons had no way of knowing it, the Ukrainian bureaucracy would quickly quash Teresa’s original plan to adopt Anatoly. Because someone at the orphanage in Dzerzhinsk had placed a child with no regard to the official guidelines, the government downgraded it to a foster home. Children from Dzerzhinsk were no longer eligible for adoption.

Not to be deterred, the Fillmons decided to travel to Dzerzhinsk first to drop off seven 70-pound bags of humanitarian aid they were carrying. The trip had a second purpose as well, they say. “Someone told us that since there had been a bad adoption out of that orphanage, we should talk to the mayor.” Perhaps he would be willing to help them circumvent normal channels and adopt the child Teresa had met earlier. The plan was a miserable failure. For Teresa, it was back to Kiev and the Adoption Center following a passionately negative response to their proposal.

“We knew from the beginning that this (the adoption) was God’s will,” Rich Fillmon says. “We also knew that these obstacles were put in our way just to distract us.” Reassurance also came from another front. When Teresa called Howell in Prague and mentioned that the adoption might have to wait until a later trip, Howell urged her to go somewhere else. “There’s got to be a boy for you somewhere,” she urged her friend. Another traveling companion, Lyuba Yenatska, a Russian translator from Gainesville, pushed the Fillmons to at least try other cities.

Back in Kiev, following her first shower in six days, Teresa Fillmon visited the Adoption Center again, trying to determine her options and make some decisions. Tamara Kunko, the center’s administrator, was adamant that the orphanage at Dzerzhinsk was no longer an option. “It was the Ukrainian equivalent of ‘What part of no don’t you understand?’” Teresa recalls.

Twenty-Two Hours on a Train

Mrs. Kunko offered pictures of several 3- and 4-year-old boys, children of the Fillmons’ target age and gender. The orphanage in Mariupol had six boys who qualified, Teresa says; she felt as if that would give them a greater chance to find the child they were seeking. It was back to the station for another train ride, this one 22 hours long. Rich and the children remained in Dzerzhinsk after deciding it would be easier if only one person made the return trip.

The Ukrainian adoption system had Teresa on a tight schedule. All paperwork related to adoption is processed in Kiev, and once she selected a child, she was responsible for delivering the necessary papers to the Adoption Center. Since faxing was out of the question (the group saw only one fax machine during its entire stay in Ukraine), that meant another grueling train ride back to Kiev as soon as the child was chosen. There were other challenges as well – Teresa arrived in Mariupol around 4:30 on a Thursday afternoon; the last train of the week returned to Kiev at 5:50! “I had 20 minutes to select my child.”

Because she wanted to observe them in as natural an environment as possible, Teresa asked the boys’ teacher to simply lay her hands on those children who were eligible for adoption. One by one, she pointed out the children from whom Teresa could choose. Some did not look well, and others seemed to have difficulty relating to their peers. Soon Artur, a small boy with gleaming eyes and a captivating smile, entered the room. His self-confidence and personality were readily apparent. When the teacher indicated that he could be adopted, Teresa quickly chose him as her son.

With Artur’s paperwork in hand, Teresa made it to the train station just in time to send the papers on the 22-hour journey back to Kiev. They arrived on a Friday afternoon, too late to be processed. Then Rich and the children took the 2 a.m. train to Mariupol to join Teresa. They met their new son and brother for the first time when Teresa arranged for Artur to spend the night with them in a hotel.

Learning the Art of the Deal

The whirlwind of paperwork and legal approvals intensified. Next, the Fillmons needed a court date before a Ukrainian judge so that the adoption could be approved. March 8 was their target, but that was Women’s Day, a national holiday in Ukraine. (Because many men work hazardous jobs and die young, the role of women assumes great significance in Ukraine. Women fill many essential government positions.) They finally were scheduled to meet the judge March 9 to finalize Artur’s adoption.

Even securing the appointment proved to be a lesson in negotiating, Ukrainian style. “At first, we thought the judge looked solid,” Rich recalls, “but then he started throwing up stumbling blocks – ‘I’m a very busy man; I can’t possibly work you in.’ – things like that. I began to realize he wanted a gift!”

Giving a gift isn’t all that unusual in Ukraine, but it does take a little finesse, Rich says. While public officials may appreciate a little extra money now and then, they are highly insulted if you just offer it to them up front. With a little help from their translator, Lyuba, the Fillmons compensated the judge and got a 4 p.m. appointment the following day. When Artur’s adoption was finally approved at 5:30, they knew they were coming down the home stretch.

front. With a little help from their translator, Lyuba, the Fillmons compensated the judge and got a 4 p.m. appointment the following day. When Artur’s adoption was finally approved at 5:30, they knew they were coming down the home stretch.

Thanks to the delays as the trip began, it was time for Rich, Dallas, Lydia and Haley Fillmon to return home. Rich was expected back at work as security director for the J.C. Penney store in Governor’s Square, and the children had exhausted their leaves of absence from Gilchrist Elementary and Raa Middle School.

Artur Meets Arthur

“Before we left, Teresa was sorting through a suitcase of clothes we had brought with us for the child we’d adopt,” Rich says. “All of a sudden I heard her gasp – she said something like, ‘Oh, my goodness!’” While sorting out the clothing she would keep for Artur, Teresa had found a T-shirt decorated with Arthur, the bespectacled aardvark familiar to so many American children through television. Ironically, the Fillmons say, Artur is Russian for Arthur.

Teresa, by now on her own, stayed in Mariupol to finish the legal work. (“I got his passport at 4:45 and had to be on the train back to Kiev at 5:55.”) When she went to pick up her son for the trip home, she worried how well he would make the transition. Would he miss his schoolmates? Would he cry after being separated from his caregivers?

“When Teresa arrived at the orphanage to pick him up,” Rich says, “she was worried that he might cry or want to stay with his classmates. Instead, she told me, he put his hand firmly in hers and never even looked back.” He remained cheerful even during the long train ride back to Kiev and the ensuing trip through Poland (where Teresa had to pick up Artur’s visa) and on to Atlanta and Tallahassee.

Today, the Fillmon family is settling in. A sunny child, Artur is learning English and, for the time being, he communicates well either in Russian or with a wide smile and lots of hugs. Based on their experience, Rich and Teresa say it’s possible to adopt a child from outside the United States without an attorney’s assistance, and they plan to share their knowledge with others interested in international adoption. “We know that you can do it yourself,” Teresa says, “for relatively little money.”

Remember, they say, “The key is to get those children out of there.”

Postscript:

The Fillmons returned in December of 2002, returning in January 2003 with their daughter Alla.